The Realities of Employment Discrimination for Disabled People

by Blog Writers

By Leah Smith

By Leah Smith

In 1988, October was established by Congress as Disability Employment Awareness Month. The goal of this designated month is to “raise awareness about disability employment issues and to celebrate the contributions of workers with disabilities.” Inarguably, one of the biggest employment issues facing the disability community today is employment discrimination.

According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “employment discrimination is to treat someone differently, or less favorably, for some reason.” This unfair treatment can be because of your race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, disability, age (age 40 or older), or genetic information.

Of course, there are hundreds of different types of disabilities and ways in which they might impact employment opportunities. Disabilities can be cognitive, physical, and/or emotional, and often limit one or more major life activities.

It is also important to note the definition of ‘major life activities.’ A major life activity is something you do every day, including your body’s own internal processes. Some examples include:

- Actions like eating, sleeping, speaking, and breathing

- Movements like walking, standing, lifting, and bending

- Cognitive functions like thinking and concentrating

- Sensory functions like seeing and hearing

- Tasks like working, reading, learning, and communicating

- The operation of major bodily functions like circulation, reproduction, and individual organs

As of July 2024, the employment rate for people with disabilities was 37%, compared to 75% among their nondisabled counterparts. After looking at cases of disability employment discrimination, we can see that it usually falls within one of the 6 following categories:

- Hiring Discrimination: When qualified applicants are not hired based on their disability, rather than their skills or qualifications.

- Wage Discrimination: When employees are paid less than their colleagues for performing the same job because of their disability.

- Promotion Discrimination: When an employee is overlooked for promotions or advancements due to their disability.

- Harassment: A work environment where an employee is subjected to unwanted comments, jokes, or behaviors based on their disability creating a hostile or intimidating work atmosphere.

- Failure to Accommodate: When an employer fails to provide reasonable accommodations to employees with disabilities.

- Termination or Demotion: When employees are unfairly fired, demoted, or forced to quit due to their disability.

Of course, any one of these forms of discrimination can also happen at the intersection of other marginalized identities, only further impacting the individual and the organization. Being the recipient of employment discrimination can have long-term emotional, financial, and psychological impacts on someone’s life; however, it can also cause reduced productivity, cause higher turnover rates, have legal and financial repercussions, and cause a lack of diversity and inclusion within an organization. The term ‘intersectionality’ was coined by professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics “intersect” and overlap with one another. As this term has evolved, she has further explained, “Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times, that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.”

Of course, any one of these forms of discrimination can also happen at the intersection of other marginalized identities, only further impacting the individual and the organization. Being the recipient of employment discrimination can have long-term emotional, financial, and psychological impacts on someone’s life; however, it can also cause reduced productivity, cause higher turnover rates, have legal and financial repercussions, and cause a lack of diversity and inclusion within an organization. The term ‘intersectionality’ was coined by professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics “intersect” and overlap with one another. As this term has evolved, she has further explained, “Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times, that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.”

Employment discrimination, particularly when viewed through an intersectional lens, underscores the severity of this issue.

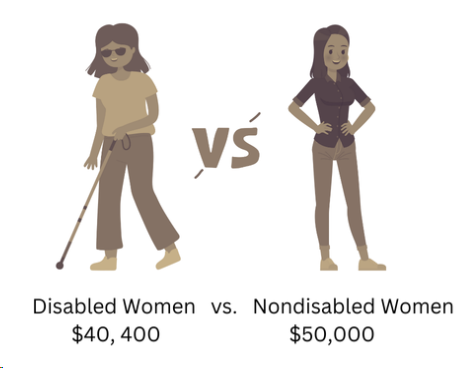

For example, we see a 20% wage gap between median annual earnings among nondisabled and disabled women in the United States.1 This breaks down to be about a $10,000 wage gap between nondisabled and disabled women ($40,400 compared to $50,000). (US Census Bureau, 2020)

For example, we see a 20% wage gap between median annual earnings among nondisabled and disabled women in the United States.1 This breaks down to be about a $10,000 wage gap between nondisabled and disabled women ($40,400 compared to $50,000). (US Census Bureau, 2020)

This also means that, overall, disabled women are only paid .50 for every dollar a nondisabled man makes. (US Census Bureau, 2020)

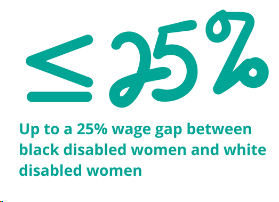

Further, the wage gap between white disabled women and black disabled women highlights the intersection of race, gender, and disability in the labor market. On average, there is a 10-25% wage gap between black women with disabilities and white women with disabilities. Factors such as education, location, and type of disability can impact this figure.

According to another study, disabled transgender individuals are 5 times more likely than nondisabled cisgender individuals to report being unemployed and looking for work for more than a month. These data only further highlight Crenshaw’s point about how intersectionality shows ‘where power comes and collides.’

As a disabled woman, I find the above statistics to be sobering. But I couldn’t help but want real stories of real people I knew. So, like any good millennial, I took it to social media. As a disabled woman, employee, and mom, I asked over 1,400 friends, “what has employment discrimination looked like for you?” I received over 77 responses like:

As a disabled woman, I find the above statistics to be sobering. But I couldn’t help but want real stories of real people I knew. So, like any good millennial, I took it to social media. As a disabled woman, employee, and mom, I asked over 1,400 friends, “what has employment discrimination looked like for you?” I received over 77 responses like:

- “Being told that they should have hired a nondisabled person instead.”

- “Prior to the pandemic, jumping through a ton of hoops and needing to disclose private medical information to have partial work-from-home status, but it took a pandemic that killed millions for work-at-home to be approved/acceptable.”

- “Given a hard ‘no’ because they were afraid I would get hurt due to heavy lifting and/or moving products around. Then given a teddy bear to make up for it.”

- “Told I was really lucky to have a job, as any other place would fire me for all of the accommodations I needed.”

- “After I finished undergrad, the job search process was hell! I would go in for interviews and would get stares. I would be qualified for positions and literally get ghosted from employers.”

- “I asked for an office chair that fits my body, and the response was ‘maybe you can just do something about your desk or how you’re sitting instead?’”

- “Being given the nickname ‘Eeyore’ by a boss because of my mental health disabilities.”

- “Was fired outright when they found out my label/disability.”

- “Supervisor telling HR I was refusing to do my job because I couldn’t do it without the reasonable accommodation they were denying.”

- “Being told that spending money to train me was a waste of resources, I’d never be management material. Then when I was a manager, moving my office to the former storage room because ‘watching you type is painful.’ I’ve been told that people like me don’t need to work because we can just live off federal disability, so I shouldn’t take a job away from someone with a family.”

- “Attending interviews where members of the interviewing panel asked how I dress myself and about my spouse.”

While many of us are aware that laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act are key pieces of legislation that provide some legal protections against disability discrimination, I would argue that, clearly, we haven’t done enough yet. Organizations like The National Center for Disability, Equity, and Intersectionality and American Progress, among many others, are advocating for key legislation that would end subminimum wage, get rid of asset limits for public assistance programs, increase funding for home and community based services, and pass the Equality Act as methods of helping to solve this problem. As Michelle Obama recently said, we just need to ‘Do Something!’

Leah Smith is the Associate Director of The National Center for Disability, Equity, and Intersectionality and Co-Facilitator for Her Power!, a national event aimed at teen girls with disabilities. She wears many hats, but being a mom to her two kids is, by far, the most important.

Leah Smith is the Associate Director of The National Center for Disability, Equity, and Intersectionality and Co-Facilitator for Her Power!, a national event aimed at teen girls with disabilities. She wears many hats, but being a mom to her two kids is, by far, the most important.

By Andrea Jennings

By Andrea Jennings  Practical Measures to Enhance Accessibility in Ground Transportation

Practical Measures to Enhance Accessibility in Ground Transportation Air and Sea Travel Accessibility

Air and Sea Travel Accessibility Andrea Jennings, M.Mus.,

Andrea Jennings, M.Mus.,

Ashira Greenberg (she/her/hers) graduated with her Master of Public Health from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and received her CHES certification. Ashira is passionate about child, youth and family health with an interest in improving educational and healthcare experiences for all young people. Ashira is especially committed to advocacy and health promotion on behalf of youth with disabilities, chronic illness and complex health needs.

Ashira Greenberg (she/her/hers) graduated with her Master of Public Health from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and received her CHES certification. Ashira is passionate about child, youth and family health with an interest in improving educational and healthcare experiences for all young people. Ashira is especially committed to advocacy and health promotion on behalf of youth with disabilities, chronic illness and complex health needs.

By Grant Stoner

By Grant Stoner

Jane, an Easterseals supporter, hadn’t updated her will in 15 years. She told the Easterseals Planned Giving team that her intention was to include a bequest to benefit Easterseals.

Jane, an Easterseals supporter, hadn’t updated her will in 15 years. She told the Easterseals Planned Giving team that her intention was to include a bequest to benefit Easterseals.